Gender is seen as flexible in many Indigenous cultures across the Americas, which is very different from how things are seen in the West.

The Zapotec community in Oaxaca, Mexico, is one of the best examples. There are three genders recognized there: men, women, and muxes, a respected third gender that comes from traditional beliefs in balance and harmony.

David Kelvin Santos, a muxe who now lives in San Francisco, is proud to carry on this practice.

I buy dresses for my sister because I like them.” I do not dress up. David told the man through a translator, “I am a Muxe nguiju. We are the men who wear pants and guayaberas.

David said there are two kinds of muxes: gunaa, who were born male but think of themselves as female, and nguiju, who are men who are attracted to other guys, like himself.

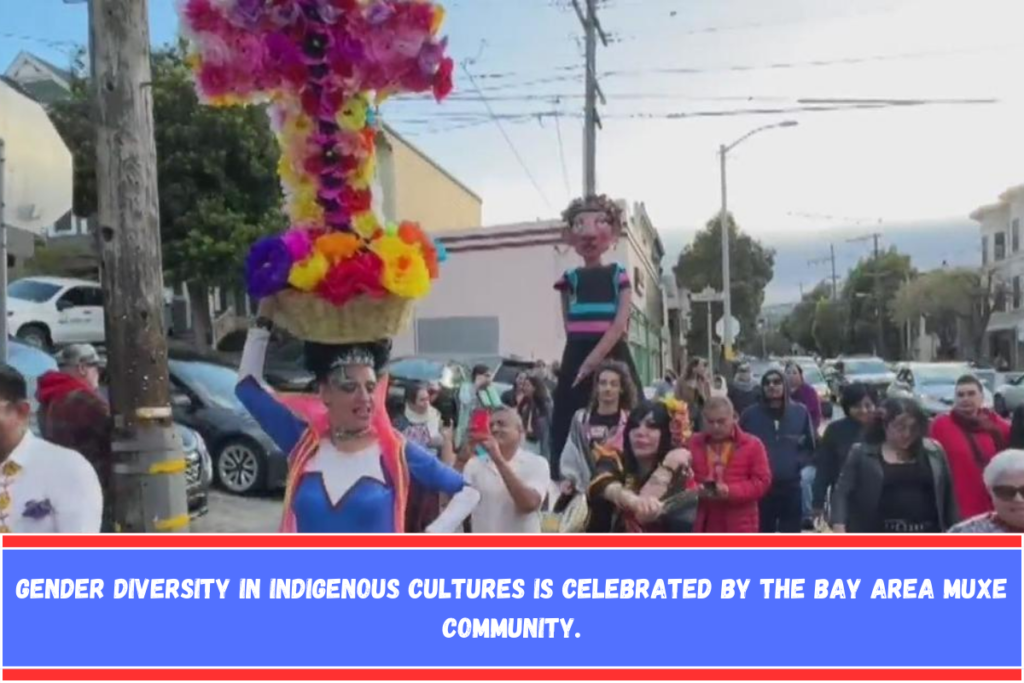

He had a great time planning the first Vela Muxe parade in San Francisco, which brought muxes together to celebrate who they were.

“A beautiful Vela with a Calenda.” He said, “For the first time, the Muxes walked through San Francisco.” The event included lively processions with dancing and music in the streets of the city.

Different genders are not just a problem in the Zapotec society. Two-spirit people, who have both male and female traits, have traditionally held important spiritual or leading roles in many Native American cultures.

In California, these people used to be called Joyas. They did jobs that women normally did, married men, and slept with both men and women. In contrast to Zapotec society, however, these jobs are not as well known today.

“The bravery of the people in Juchitán to protect their culture—that’s what has allowed the third gender to survive,” David said, stressing how important it is for cultures to be able to bounce back from setbacks.

Vinal Antonio Lopez, who is also a muxe from Oaxaca but now lives in Oakland, talked about how far muxes have come over the years.

“Things were very different fifty or forty-five years ago.” “The Muxe was destined to work in a cantina… there weren’t many chances,” Vidal said, pointing out the progress made toward more acceptance and chances.

Felina Santiago, a well-known muxe gunaa in Juchitán, thought about how the way muxes show their identity has changed over time. She said that muxes today are more open about how they look than they were in the past.

“In the past, muxes were quieter.” They didn’t put on any makeup. They weren’t dressed up. They didn’t let their hair get really long… “Yes, we’ve always been here, but they dressed and walked differently because they didn’t have the internet or TV,” Felina said.

Even with these celebrations of identity, muxes still have to deal with a lot of problems. Letra S, an advocacy group, says that between 2018 and 2022, more than 450 LGBTQ+ people, including muxes, were killed in Mexico.

Even though things are hard, the muxe community is still eager to keep their traditions alive.

“Nostalgia kills those of us who move.” “We miss our roots very much, and we need to find something to hold on to so we don’t feel like we’re adrift, like a ship lost at sea,” David said, expressing the longing and strength of those who continue to enjoy their heritage far from home.

The Vela Muxe party is still an important part of the culture because it brings people together through dance, music, and community service.

It’s more than just a get-together; it’s a powerful way to honor the past of Native American and Zapotec traditions and bring people from different cultures together.

The fact that the next Vela Muxe will happen in May shows how strong the muxe community is and how important it is to pass on these rich cultural traditions to future generations.